Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

The distrust of doctors and government that feeds the anti-vaccination movement might be seen as a modern phenomenon, but the roots of today’s activism were put down well over a century ago.

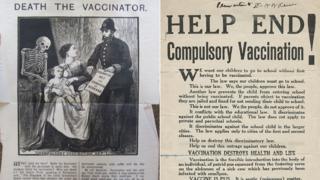

In the late 19th Century, tens of thousands of people took to the streets in opposition to compulsory smallpox vaccinations. There were arrests, fines and people were even sent to jail.

Banners were brandished demanding “Repeal the Vaccination Acts, the curse of our nation” and vowing “Better a felon’s cell than a poisoned babe”. Copies of hated laws were burned in the streets and the effigy was lynched of the humble country doctor who was seen as to blame for the smallpox prevention programme.

Warning – this story contains graphic images

At the height of this fight, the people of Leicester, a city in the English Midlands, claimed to have found an alternative to vaccination – and it’s an approach that is still quoted by campaigners today.

The shockwaves from this storm of anti-establishment anger went far beyond the streets of Leicester and the group behind it, formed 150 years ago.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

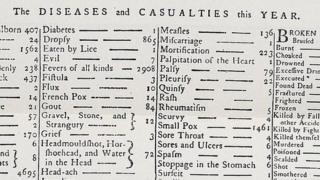

Smallpox, called the “speckled monster” due to its distinctive blister-like rashes, had killed millions since medieval times.

At one stage it was the single biggest cause of death in Europe, killing 400,000 every year. In the Americas it ravaged native tribes and entire cultures collapsed.

A third of survivors were blinded. Almost all who did not die were scarred for life.

So why did a cheap and apparently effective solution – vaccination – threaten to tear society apart?

Image copyright Global Freedom Movement

Image copyright Global Freedom Movement

The story starts in 1798 with Gloucestershire doctor Edward Jenner successfully testing the country-lore that a dose of relatively mild cowpox infection gave protection from smallpox.

Within five years, Jenner’s discovery was being used across Europe and a decade later it had gone global.

But opposition was swift and savage. Why?

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

“This came from a variety of angles – sanitary, religious, scientific and political,” said medical historian Dr Kristin Hussey.

“Some felt the method – using material from cows – was unhealthy or unchristian, using matter from lower creatures.

“Some disputed smallpox was passed from person to person, but many simply objected to being told what was good for them.”

There followed a 100-year battle between the authorities and an often sceptical, sometimes aggressive, public.

In Britain, a succession of laws made vaccinations free, then compulsory – backed by fines and even imprisonment. While riots flared in some towns, there was also more restrained opposition in the form of anti-vaccination leagues.

For an increasingly literate population, pamphlets were produced with titles like “Vaccination: its fallacies and evils”, “Vaccination, a Curse” and the suitably Gothic “Horrors of Vaccination”.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

Dr Hussey said: “In modern terms, it was a very ‘woke’ time.

“People were asking questions about rights, especially working-class rights. There was a sense the upper classes were trying to take advantage, a feeling of distrust.

“This was a move into an area of people’s private lives, their health, which had not been governed before.

“And vaccines were not as safe as they are now – people did become seriously ill and even died. If I was alive at the time I would have been wary of vaccinations too.”

Supporters pointed to falling death rates and milder occurrences of the disease, while opponents highlighted continued outbreaks and the appalling side effects of vaccination, such as abscesses and cross infections.

Victorian medicine

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

Never was the lie of “the good old days” more clear than in medicine.

The 1841 UK census suggested a third of doctors were unqualified. An 1848 medical book claimed common causes of illness were “diseased parents”, night air, sedentary habits, wet feet and abrupt changes of temperature.

It stated cholera, a scourge of Victorian society, was caused by rancid food, “cold fruits” like cucumbers and melons, and passionate fear or rage.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

In 1850 the average life expectancy was not much above 40 years, and 15% of children died before the age of one.

The 1858 Medical Act brought in standards and registration but this was at a time when the majority of professionals still believed bad air – miasma – caused many illnesses.

Germ theory – that microscopic organisms invading the body can cause disease – was not widely accepted until the 1880s.

Alongside qualified medics were the quacks and traditional healers – and without a health service, everyone charged for their services, excluding many from all but the most basic care.

At this point, immunisation was still in its infancy and naturally produced cowpox material varied in quality.

What is more, it took decades to realise vaccination failed to give lifelong immunity, while clumsy procedures could lead to secondary infections, such as syphilis, hepatitis and tuberculosis.

The Leicester Anti-Vaccination League was set up in 1869 but the approach that would be lauded by those opposed to vaccination came in 1877, ironically enough, from the medical establishment.

- How smallpox claimed its final victim

- The countries that trust vaccines the least

- Bug busters: The tech behind new vaccines

The city medical examiner made it compulsory to report cases of smallpox. He would then isolate the patient, quarantine family and disinfect – and sometimes burn – belongings.

Originally designed to work alongside vaccination, the League promoted it as an alternative and the “Leicester method” sparked growing defiance.

Timeline

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

1796 – Edward Jenner successfully tests the idea that cowpox protects against smallpox

1805 – First attempt at compulsory vaccination, in Italy, fails

1820 – Smallpox deaths in London fall significantly

1840 – Vaccination Act makes vaccinations free

1853 – New Vaccination Act makes vaccination compulsory in the first three months of a child’s life

1867 – Vaccinations compulsory for all children below 14

1869 – Leicester Anti-Vaccination League founded

1885 – Mass protest held in Leicester

1898 – Vaccination Act introduces “conscientious objection” clause

Science writer Jason “The Germ Guy” Tetro sees powerful echoes in today’s controversy.

“We tend to hear civil rights as a major factor in detractors’ arguments,” he said. “They feel the government is imposing too many restrictions on their liberties by invoking mandatory vaccinations.

“This is similar to what was heard in Leicester. However, the resolution back then happened to be the removal of individual rights for the sake of the population.

“That was the law. I am not sure how that would go over in today’s world.”

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

In Leicester the number of prosecutions for non-vaccination grew from two in 1869 to 1,154 in 1881 and about 3,000 in 1884.

Figures for the second half of 1883 showed in Leicester, of 2,281 births only 707 babies were vaccinated.

Court cases provided incendiary publicity for the anti-vax movement.

Image copyright College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Image copyright College of Physicians of Philadelphia

In March 1884, resident George Bamford told magistrates his three eldest children had been vaccinated. Two had been confined to bed for days and a third had died.

For refusing to vaccinate his fourth child, he was ordered to pay 10 shillings – half the average weekly wage – or spend seven days in prison.

Fines were fiercely enforced. Police collecting a fine from one Arthur Ward threatened his pregnant wife with prison. The argument sent her into premature labour and the child was stillborn.

Image copyright Jenner Trust

Image copyright Jenner Trust

In October 1884 the Leicester Board of Guardians asked the London authorities for an easing of prosecutions, in the light of the Leicester method. The request was rejected, setting the stage for the city’s mass protest of 1885.

Although peaceful, the scale of the demonstration shook the establishment. Medical professionals feared for the unvaccinated city, predicting “a terrible nemesis would overtake it in the shape of a disastrous epidemic”.

Smallpox duly returned between 1892 and 1894. And the result shocked many.

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

Image copyright Wellcome Trust

Leicester actually escaped relatively lightly, with 370 cases – a rate of 20.5 cases per 10,000 of the population – resulting in 21 deaths. This was a far lower figure of cases than in some well-vaccinated towns like Warrington (125) and Sheffield (144).

Anti-vaccinationists were triumphant, claiming the Leicester method had been proven.

Dr Tetro said: “The so-called marvellous success of the Leicester method was based on the fact it used a tried and true method of notification and quarantine in combination with the benefit of a hospital and the use of a type of ring vaccination in which healthcare staff were vaccinated.

“In a small population, this can work but as the population grows, this method becomes untenable.

“This was seen in 1893 when people had to resort to staying at home instead of being cared for in a hospital during an epidemic that led to hundreds of infections.”

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

The flip side was that in London – where vaccination was widespread – there was success in containing smallpox, with 5.5 cases per 10,000 people. And some poorly vaccinated places, like Dewsbury (339 cases) and Gloucester (501), were badly hit.

And Leicester had the highest proportion of cases – more than two thirds – in under 10s.

Nonetheless, the headlines and protests, along with a growing understanding of how diseases spread, resulted in significant change.

In 1898 a new Vaccination Act introduced a clause allowing people to opt out for moral reasons – the first time “conscientious objection” was recognised in UK law.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

The following year, notification of various infectious diseases, including smallpox, became compulsory. And while smallpox returned to Britain in the early 20th Century, it never carried the same threat.

As the use of vaccines spread – along with improved sanitation – smallpox was pushed out of Europe and North America.

A World Health Organization (WHO) global eradication programme was launched in 1959 and intensified in 1967. Apart from a death linked to a Birmingham laboratory, the last case was recorded in Somalia in 1977.

Image copyright Twitter

Image copyright Twitter

However, opposition to vaccines – questioning their efficiency and safety – continues. Some campaigners hold up the Leicester method as evidence society can cope without such intervention.

Alarm bells were sounded recently with the news that routine vaccinations for under-fives fell last year.

Compulsory vaccination is still bitterly debated. Parts of the medical profession, such as the Royal College of Paediatrics, believe it would be counterproductive and make people more suspicious.

Earlier this year, the WHO declared “vaccine hesitancy” as one of the top 10 threats to global health.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

Owen Gower, the manager of the Jenner’s House Museum, reflected on the country doctor’s legacy.

“Countless deaths and incidences of the severe scarring and blindness that the disease could cause have been averted, thanks to Jenner’s discovery and his determination to tell the world about it.

“Now we have the opportunity to do the same with other diseases. Further vaccines, developed after Jenner’s death, save an estimated two to three million lives every year.

“Jenner’s legacy is a world where we do not have to live in fear of horrific infectious diseases.”

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk.

Original Article : HERE ;

from MetNews https://metnews.pw/victorian-englands-anti-vaccination-movement/

No comments:

Post a Comment